Pictured: "Writers' Bloc" cover story from the Pittsburgh City Paper.My feature about Pittsburgh graffiti received a letter to the editor last week. Written by a local gentleman named Jacob Bacharach, the letter offers an entirely different perspective on graffiti. Although Mr. Bacharach's reply is wordy and spends a good bit of time stroking his own ego (it appears someone spent some time in academia), his veiled insults and the rare moments when a cohesive thought arises from the twisted wreckage of his sentences offers readers a counterpoint of sorts. Please feel free to include your comments about graffiti culture and/or Bacharach's response in the "comments" portion of this post. I've also included some seen and unseen photos from the story in this post.

Pictured: "Writers' Bloc" cover story from the Pittsburgh City Paper.My feature about Pittsburgh graffiti received a letter to the editor last week. Written by a local gentleman named Jacob Bacharach, the letter offers an entirely different perspective on graffiti. Although Mr. Bacharach's reply is wordy and spends a good bit of time stroking his own ego (it appears someone spent some time in academia), his veiled insults and the rare moments when a cohesive thought arises from the twisted wreckage of his sentences offers readers a counterpoint of sorts. Please feel free to include your comments about graffiti culture and/or Bacharach's response in the "comments" portion of this post. I've also included some seen and unseen photos from the story in this post. Pictured: ONOROK freight; photo courtesy of PRISM.Bloc heads

Pictured: ONOROK freight; photo courtesy of PRISM.Bloc heads

Were it not for the sympathetic fatuity of the Matthew Newtons of this world [“Writers’ Bloc,” Nov. 22], graffiti would now occupy its rightful place in the pantheon of visual mediums -- just above the works of Thomas Kinkade, just below the occasionally lovely works of our better painters-by-number.  Pictured: Force One wall piece; photo courtesy of Sesk.

Pictured: Force One wall piece; photo courtesy of Sesk.

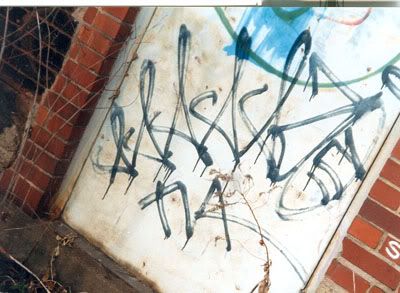

Unfortunately, Newton isn’t alone in the delusion that illegality confers authenticity, nor is he alone in believing that historicity indicates legitimacy. He believes, as do too many other crass revolutionaries, that prohibitions of actions inherently commend them to practice. That most graffiti writers can at best manage black-line tags scrawled ad infinitum on squalid alley walls and street signs is irrelevant to such judgments. Merit is irrelevant. Newton sees the amateurish shadows on the wall and intuits himself to the perfect Platonic forms in the light near the mouth of the cave. In all the pieces featured in his story, the nearest approach to political content is the predictable transposition of “ph” for “f.” First Webster’s, then the world!

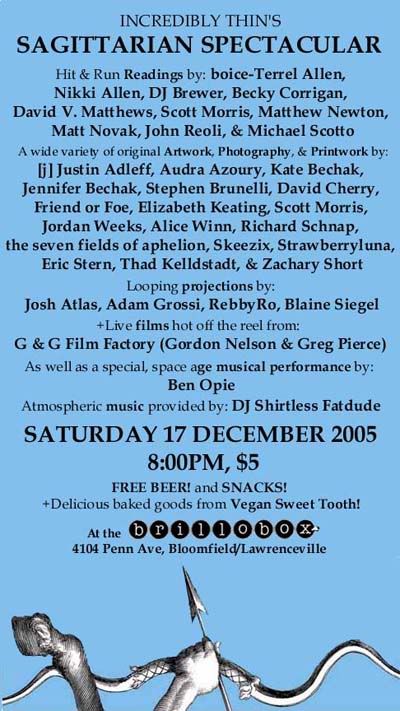

Pidtured: AZO 2 tag; photo courtesy of Sesk.

Pidtured: AZO 2 tag; photo courtesy of Sesk.

I’m generally a fan of rebellion against the behavioral strictures of the state, aesthetically and otherwise. Every decent observer of American culture since de Tocqueville has come away with the same caveats about the stultifying conformity of Americans’ social and cultural lives. But graffiti isn’t illegal because a sinister cabal wishes to quash a fountainhead of youthful creativity. It isn’t reprobated because it offends some imaginary bourgeois sensibility of the philistine masses.

Pictured: Prism wall piece; photo courtesy of Prism.

Pictured: Prism wall piece; photo courtesy of Prism.

Graffiti is legally, aesthetically and culturally anathema because so much of it is so very ugly and bad.

Whatever political content and social relevance the form may have once possessed, it’s now devolved into the sort of asinine look-at-me-ism that wouldn’t be out of place on a second-rate hip-hop album. As for its aesthetic aspect, elaborate spray-painted graffiti was appropriated and subverted by high art and its expensive galleries before the end of the ’80s. It was never terribly original to begin with, and now, a couple of decades later, its callow and repetitive style is both empty and embarrassing. Note that in his introduction and the several pages of interviews that follow, Newton says next to nothing about the so-called art featured so prominently in the photographs. He fails to do so for a single overriding reason: There’s nothing to say.

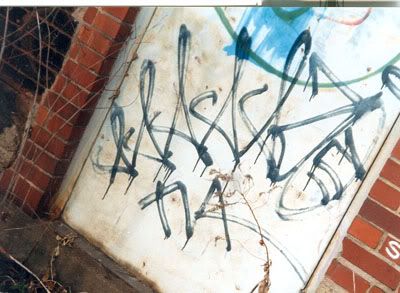

Pictured: "Reunion" piece in Pittsburgh early 1980s (artist unknown); photo copyright Henry Chalfant.

Pictured: "Reunion" piece in Pittsburgh early 1980s (artist unknown); photo copyright Henry Chalfant.

In Pittsburgh, at least one gallery opened a show featuring many of graffiti’s supposed artists -- only to find its own exterior walls crudely tagged the next morning. Perhaps it was the Pabst. (Actually, it’s almost always the Pabst, which, like absinthe before it, is more useful to pretenders to an art than to actual artists.)

Graffiti isn’t art; it’s vandalism. What’s more, it isn’t vandalism for any political purpose other than the petulant, adolescent insistence that the standards of decent behavior toward one’s own community don’t apply simply because they’re standards. It’s childish and destructive, and to find such childish destruction trumpeted as a venerable tradition in the pages of a publication ostensibly concerned with the uplift of the city of Pittsburgh is most depressing of all.

-Jacob Bacharach, Lawrenceville